Abstract

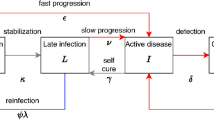

Several human-adapted Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (Mtbc) lineages exhibit a restricted geographical distribution globally. These lineages are hypothesized to transmit more effectively among sympatric hosts, that is, those that share the same geographical area, though this is yet to be confirmed while controlling for exposure, social networks and disease risk after exposure. Using pathogen genomic and contact tracing data from 2,279 tuberculosis cases linked to 12,749 contacts from three low-incidence cities, we show that geographically restricted Mtbc lineages were less transmissible than lineages that have a widespread global distribution. Allopatric host–pathogen exposure, in which the restricted pathogen and host are from non-overlapping areas, had a 38% decrease in the odds of infection among contacts compared with sympatric exposures. We measure tenfold lower uptake of geographically restricted lineage 6 strains compared with widespread lineage 4 strains in allopatric macrophage infections. We conclude that Mtbc strain–human long-term coexistence has resulted in differential transmissibility of Mtbc lineages and that this differs by human population.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The raw sequences were deposited at the European Nucleotide Archive or the Sequence Read Archive at the National Center for Biotechnology Information under BioProject identifiers PRJEB9680, PRJNA766641 and PRJNA882748. Accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table 13. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code used in this study was previously published and is publicly available as cited in Methods. No custom code was developed or used.

References

Brites, D. & Gagneux, S. Co-evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Homo sapiens. Immunol. Rev. 264, 6–24 (2015).

Stucki, D. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage 4 comprises globally distributed and geographically restricted sublineages. Nat. Genet. 48, 1535–1543 (2016).

Merker, M. et al. Evolutionary history and global spread of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing lineage. Nat. Genet. 47, 242–249 (2015).

Hirsh, A. E., Tsolaki, A. G., DeRiemer, K., Feldman, M. W. & Small, P. M. Stable association between strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and their human host populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4871–4876 (2004).

Demay, C. et al. SITVITWEB—a publicly available international multimarker database for studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. Infect. Genet. Evol. 12, 755–766 (2012).

Wiens, K. E. et al. Global variation in bacterial strains that cause tuberculosis disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 16, 196 (2018).

Roetzer, A. et al. Whole genome sequencing versus traditional genotyping for investigation of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreak: a longitudinal molecular epidemiological study. PLoS Med. 10, e1001387 (2013).

Holt, K. E. et al. Frequent transmission of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing lineage and positive selection for the EsxW Beijing variant in Vietnam. Nat. Genet. 50, 849–856 (2018).

Grosset, J., Rist, S. S. & Meyer, N. Cultural and biochemical characteristics of tubercle bacilli isolated from 230 cases of tuberculosis in Mali. Bull. Int. Union Tuberc. 49, 177–187 (1974).

De Jong, B. C. et al. Use of spoligotyping and large sequence polymorphisms to study the population structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in a cohort study of consecutive smear-positive tuberculosis cases in the Gambia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 994–1001 (2009).

Asante-Poku, A. et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium africanum in Ghana. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 385 (2016).

Chakravarti, A. et al. Indigenous transmission of Mycobacterium africanum in Canada: a case series and cluster analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6, ofz088 (2019).

Firdessa, R. et al. Mycobacterial lineages causing pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Ethiopia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 460–463 (2013).

Gagneux, S. et al. Variable host–pathogen compatibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2869–2873 (2006).

Comas, I. et al. Out-of-Africa migration and Neolithic coexpansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with modern humans. Nat. Genet. 45, 1176–1182 (2013).

Bos, K. I. et al. Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis. Nature 514, 494–497 (2014).

Kay, G. L. et al. Eighteenth-century genomes show that mixed infections were common at time of peak tuberculosis in Europe. Nat. Commun. 6, 6717 (2015).

Sabin, S. et al. A seventeenth-century Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome supports a Neolithic emergence of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Genome Biol. 21, 201 (2020).

Vågene, Å. J. et al. Geographically dispersed zoonotic tuberculosis in pre-contact South American human populations. Nat. Commun. 13, 1195 (2022).

Pepperell, C. S. et al. The role of selection in shaping diversity of natural M. tuberculosis populations. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003543 (2013).

Reed, M. B. et al. Major Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineages associate with patient country of origin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 1119–1128 (2009).

Hershberg, R. et al. High functional diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis driven by genetic drift and human demography. PLoS Biol. 6, e311 (2008).

Namouchi, A., Didelot, X., Schöck, U., Gicquel, B. & Rocha, E. P. C. After the bottleneck: genome-wide diversification of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by mutation, recombination, and natural selection. Genome Res. 22, 721–734 (2012).

Nebenzahl-Guimaraes, H., Borgdorff, M. W., Murray, M. B. & van Soolingen, D. A novel approach—the propensity to propagate (PTP) method for controlling for host factors in studying the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 9, e97816 (2014).

World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2017 (World Health Organization, 2017).

Freschi, L. et al. Population structure, biogeography and transmissibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6099 (2021).

Baker, L., Brown, T., Maiden, M. C. & Drobniewski, F. Silent nucleotide polymorphisms and a phylogeny for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 1568–1577 (2004).

Asante-Poku, A. et al. Mycobacterium africanum is associated with patient ethnicity in Ghana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e3370 (2015).

Klinkenberg, D., Backer, J. A., Didelot, X., Colijn, C. & Wallinga, J. Simultaneous inference of phylogenetic and transmission trees in infectious disease outbreaks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005495 (2017).

HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2020 (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2020); https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/hiv-surveillance-annualreport-2020.pdf

Gounder, P. P. et al. Risk for tuberculosis disease among contacts with prior positive tuberculin skin test: a retrospective cohort study, New York City. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 30, 742–748 (2015).

Getahun, H. et al. Management of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: WHO guidelines for low tuberculosis burden countries. Eur. Respir. J. 46, 1563–1576 (2015).

Mathema, B. et al. Drivers of tuberculosis transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S644–S653 (2017).

de Jong, B. C., Antonio, M. & Gagneux, S. Mycobacterium africanum—review of an important cause of human tuberculosis in West Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e744 (2010).

Coscolla, M. et al. Phylogenomics of Mycobacterium africanum reveals a new lineage and a complex evolutionary history. Microb. Genom. 7, 000477 (2021).

Ruis, C. et al. A lung-specific mutational signature enables inference of viral and bacterial respiratory niche. Microb. Genom. 9, mgen001018 (2023).

Duffy, S. C. et al. Reconsidering Mycobacterium bovis as a proxy for zoonotic tuberculosis: a molecular epidemiological surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 1, e66–e73 (2020).

Kodaman, N. et al. Human and Helicobacter pylori coevolution shapes the risk of gastric disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1455–1460 (2014).

Gygli, S. M. et al. Prisons as ecological drivers of fitness-compensated multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 27, 1171–1177 (2021).

Shea, J. et al. Comprehensive whole-genome sequencing and reporting of drug resistance profiles on clinical cases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in New York State. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 1871–1882 (2017).

Diel, R. et al. Accuracy of whole genome sequencing to determine recent tuberculosis transmission: an 11-year population-based study in Hamburg, Germany. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01154-2019 (2019).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 (2013).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9, e112963 (2014).

Marin, M. et al. Benchmarking the empirical accuracy of short-read sequencing across the M. tuberculosis genome. Bioinformatics 38, 1781–1787 (2022).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W242–W245 (2016).

Coll, F. et al. A robust SNP barcode for typing Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Nat. Commun. 5, 4812 (2014).

Couvin, D., Reynaud, Y. & Rastogi, N. Two tales: worldwide distribution of Central Asian (CAS) versus ancestral East-African Indian (EAI) lineages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis underlines a remarkable cleavage for phylogeographical, epidemiological and demographical characteristics. PLoS ONE 14, e0219706 (2019).

Netikul, T., Palittapongarnpim, P., Thawornwattana, Y. & Plitphonganphim, S. Estimation of the global burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage 1. Infect. Genet. Evol. 91, 104802 (2021).

O’Neill, M. B. et al. Lineage specific histories of Mycobacterium tuberculosis dispersal in Africa and Eurasia. Mol. Ecol. 28, 3241–3256 (2019).

Menardo, F. et al. Local adaptation in populations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis endemic to the Indian Ocean Rim. F1000Res 10, 60 (2021).

Coscolla, M. & Gagneux, S. Consequences of genomic diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol. 26, 431–444 (2014).

Bifani, P. J., Mathema, B., Kurepina, N. E. & Kreiswirth, B. N. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol 10, 45–52 (2002).

Glynn, J. R., Whiteley, J., Bifani, P. J., Kremer, K. & van Soolingen, D. Worldwide occurrence of Beijing/W strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 843–849 (2002).

Cowley, D. et al. Recent and rapid emergence of W-Beijing strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Cape Town, South Africa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47, 1252–1259 (2008).

Källenius, G. et al. Evolution and clonal traits of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in Guinea-Bissau. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 3872–3878 (1999).

Bouke C. de Jong, Martin Antonio, Timothy Awine, Kunle Ogungbemi, Ype P. de Jong, Sebastien Gagneux, Kathryn DeRiemer, Thierry Zozio, Nalin Rastogi, Martien Borgdorff, Philip C. Hill, and Richard A. AdegbolaUse of spoligotyping and large-sequence polymorphisms to study the population structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in a cohort study of consecutive smear positive tuberculosis cases in the Gambia. J Clin Microbiol. 2009 Apr; 47(4): 994–1001

Walker, T. M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 137–146 (2013).

Jombart, T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008).

Reback, J. et al. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas 1.3.5. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3509134 (2021).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013). URL: https://www.r-project.org/

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. JOSS 4, 1686 (2019).

Finch, W. H., Finch, M. E. H. & Singh, M. Data imputation algorithms for mixed variable types in large scale educational assessment: a comparison of random forest, multivariate imputation using chained equations, and MICE with recursive partitioning. Int. J. Quant. Res. Educ. 3, 129 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Lapierre from the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York, and the Wadsworth Center Applied Genomics Technology Cluster for whole-genome sequencing and data transfer. We acknowledge H. de Neeling, H. Schimmel and E. Slump from the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, the Netherlands. We thank V. Dreyer and T. Kohl for transferring sequence data, M. Hein and T. Scholzen from the Flow Cytometry Core, F. Daduna for participant recruitment and D. Beyer and S. Maaß for technical assistance, all at the Research Center Borstel. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases R21 AI154089 to M.R.F.; the German Research Foundation (GR5643/1-1) to M.I.G.; the BIH Charité Junior Digital Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin; the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH) to M.I.G.; the Leibniz Science Campus EvoLUNG (Evolutionary Medicine of the Lung; https://evolung.fz-borstel.de/) grant number W47/2019 to F.J.P.-L., S.N. and S.H.; the German Research Foundation under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC 2167 Precision Medicine in Inflammation; and the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for the German Center of Infection Research (DZIF) to S.N. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.F. and M.I.G. conceived the idea for the epidemiological analysis. S.N., S.H. and F.J.P.-L. conceived the idea for the in vitro experiments. M.R.F. supervised the project. M.I.G. performed data curation and data analysis. M.I.G. and M.R.F. wrote the first draft. F.J.P.-L. performed data curation and data analysis. R.V.Jr. and D.K. analysed the data. L.T., P.K. and R.D. carried out data acquisition. V.E., K.M., J.S.M., S.H., D.v.S., S.D.A. and S.N. supervised data acquisition and curation. W.S. and B.M. critically reviewed the drafts. All authors reviewed the draft and assisted in the preparation of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Sebastien Gagneux, Stephen Gordon and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Genetic characteristics of M. tuberculosis complex strain.

a) Violin plot of the terminal branch lengths of the included Mtbc genetic lineages. The overlayed box plots display the median, the first and third quartile, and the horizontal lines represent the upper and lower values of the data. L1 = 523, L2widespread = 707, L2restricted = 75, L3 = 681, L4widespread = 2,494, L4restricted = 220, L5 = 17, L6 = 27 strains, respectively. b) Proportions of strains in clusters based on several different Single Nucleotide Substitution (SNS) thresholds by genetic lineage and site. L = Lineage, SNP = Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, NYC = New York City, NL = The Netherlands, HH = Hamburg, L2restricted includes sub-lineages 2.1., 2.2.2., and 2.2.1.1.2, L4restricted sub-lineages include 4.11, 4.2.1.1, 4.3.i2, 4.5, and 4.6.2.2. L2widespread refers to sub-lineages 2.2.1, 2.2.1.1, 2.2.1.1.1, 2.2.1.1.1i1, 2.2.1.1.1.i2, 2.2.1.1.1.i3, 2.2.1.2, L4 to all other L4 sub-lineages (see Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Relationship of index case self-reported ancestry and human-adapted M. tuberculosis complex lineage.

a) Bar plot detailing the proportions of isolation country and Mtbc lineage in a global sample of 25,243 strains. b) Adjusted odds ratios estimated for the variable contact allopatry using different co-localization or sympatry assumptions from multivariate Generalized Estimation Equation (GEE) models (see Fig. 3f in main text). No effect for L4widespread is shown. L2restricted includes sub-lineages 2.1., 2.2.2 and 2.2.1.1.2, L4restricted sub-lineages include 4.11, 4.2.1.1, 4.3.i2, 4.5, and 4.6.2.2. L2widespread refers to sub-lineages 2.2.1, 2.2.1.1, 2.2.1.1.1, 2.2.1.1.1i1, 2.2.1.1.1.i2, 2.2.1.1.1.i3, 2.2.1.2, L4 to all other L4 sub-lineages (see Methods). The bars represent the effect estimates from the GEE models with 95% confidence intervals. N = 2,556 contacts.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Comparison of the inflammatory response induced by M. tuberculosis complex L6 (a-b) and L4 (c-d) strains in human monocyte derived macrophages (MDMs) based on their self reported ancestry colocalizing with L6 at 24 (a-c) and 96 (b-d) hours post-infection.

Six human inflammatory cytokines-chemokines were screened using LEGENDplex. The stacked bars represent the mean production of IL-1ß, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-18. Each bar represents three donors colocalizing with strains of Lineage 6 (Yes [Nigerian, Cameroonian, Ghanaian]) and no colocalizing with strains of Lineage 6 (No [German donors]). PBS, Macrophage Infection Media (MIM), and supernatants from not infected MDMs were used as controls. The MIM values were subtracted from the not infected and infected MDMs. Mean, standard error of the mean, and significant statistical results (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001) are shown. Statistical results were calculated based on Two-way ANOVA multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction. Data were obtained from six independent infection experiments (three for each donor group). L6, Lineage 6; L4, Lineage 4; hpi, hours post-infection.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cytokine response of human macrophages of donors with self-reported ancestry to Europe to distinct Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains.

This assay was conducted on cell culture supernatants collected from MDMs that were infected with 3 representative strains of L4 and L6, and also no infected MDMs. The infection was carried out with an MOI ~ 1:1, and the supernatants were collected at 24 and 96 hours post-infection (hpi). Three infection macrophage wells were tested per strain, time point, and donor. 13 human inflammatory cytokines-chemokines were screened using LEGENDplex. The production of six detected cytokines-chemokines is depicted in the figure, namely IL-1ß (a), TNF-α (b), MCP-1 (c), IL-6 (d), IL-8 (e) and IL-18 (f). The protein concentration in pg/mL was plotted on the y-axis, while the x-axis represented the controls (PBS and no-infected [NI] at 24 hpi and 96 hpi) and experimental conditions (infected with L4, and L6 at 24 hpi and 96 hpi). The stacked bars compared the mean production of these cytokines-chemokines at 24 hpi and 96 hpi within a lineage and across lineages. Each lineage is represented by three strains (three dots), and each strain comprises the averaged values of three donors. PBS, Macrophage Infection Media (MIM), and non-infected cells were used as controls. The MIM values were subtracted from no-infected and infected wells. The mean, standard error of the mean, and statistical results (ns >0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001) are depicted in the figures. Data were obtained from three independent infection experiments. The statistical results shown in the figures are two-sided p-values based on an unpaired t-test among both time points within the same lineage strain and on one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test correction-multiple comparisons across distinct lineages at 24 hpi and 96 hpi. MDMs, Monocyte Blood Derived Macrophages; ns, not significant; NI, not-infected; L4, Lineage 4; L6, Lineage 6; CFU, Colony Forming Unit; MOI, Multiplicity of Infection; h, hours.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cytokine response of human macrophages of donors with self-reported ancestry to Ghana, Cameroon, and Nigeria to distinct Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains.

This assay was conducted on cell culture supernatants collected from MDMs that were infected with 3 representative strains of L4 and L6, and also no infected MDMs. The infection was carried out with an MOI ~ 1:1, and the supernatants were collected at 24 and 96 hours post-infection (hpi). Three infection macrophage wells were tested per strain, time point, and donor. 13 human inflammatory cytokines-chemokines were screened using LEGENDplex. The production of six detected cytokines-chemokines is depicted in the figure, namely IL-1ß (a), TNF-α (b), MCP-1 (c), IL-6 (d), IL-8 (e) and IL-18 (f). The protein concentration in pg/mL was plotted on the y-axis, while the x-axis represented the controls (PBS and no-infected [NI] at 24 hpi and 96 hpi) and experimental conditions (infected with L4, and L6 at 24 hpi and 96 hpi). The stacked bars compared the mean production of these cytokines-chemokines at 24 hpi and 96 hpi within a lineage and across lineages. Each lineage is represented by three strains (three dots), and each strain comprises the averaged values of three donors. PBS, Macrophage Infection Media (MIM), and no-infected cells were used as controls. The MIM values were previously subtracted from no-infected and infected wells. The mean, standard error of the mean, and statistical results (ns, P >0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001) are depicted in the figures. Data were obtained from three independent infection experiments. The statistical results shown in the figures are two-sided p-values based on an unpaired t-test among both time points within the same lineage strain and on one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test correction-multiple comparisons across distinct lineages at 24 hpi and 96 hpi. MDMs, Monocyte Blood Derived Macrophages; ns, not significant; NI, not-infected; L4, Lineage 4; L6, Lineage 6; CFU, Colony Forming Unit; MOI, Multiplicity of Infection; h, hours.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison of tuberculosis index case and social contact group characteristics.

a) Dot plot of the index case age (x-axis) versus mean contact group age (y-axis) for each of the included cities; b) Dot plot of the No. of M. tuberculosis infections per contact group (x-axis) and the size of the contact group (y-axis). A linear regression line is overlayed with 95% confidence intervals.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Legends for Extended Data Figs. 1–6, Supplementary Figs. 1–7 and Supplementary Tables 1–12.

Supplementary Table 13

Accession codes for sequence data used in this study.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Tree file.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4 and Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3–5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gröschel, M.I., Pérez-Llanos, F.J., Diel, R. et al. Differential rates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission associate with host–pathogen sympatry. Nat Microbiol 9, 2113–2127 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01758-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01758-y